Its an era of “The New Age of Geoeconomics”. It explains why the intersection of geo-politics and geo-economics is shaping today’s global landscape and what it means for governments, businesses, and society.

Introduction: A New Strategic Landscape

In a dramatic shift reminiscent of economic eras that preceded World Wars and protectionist eras, the world has entered a new age of geoeconomics—where economic policy is wielded as a geopolitical weapon. This resurgence reflects a departure from decades of neoliberal globalization—characterized by free trade and open markets—into a world where powerful nations like the U.S., China, and many others now operate under zero‑sum economic logic.

The term “geoeconomics,” originally coined by Edward Luttwak, describes how states use economic tools—tariffs, subsidies, sanctions, investment controls, industrial policy—not just for economic gain, but as strategic levers in global power politics. We are experiencing an intellectual shake-up: after decades of favoring economics over geopolitics, policy elites now prioritize national power, security, and relative positioning in the global order.

1. The Return of Economic Nationalism

A central trigger of this new mindset was the Trump-era trade war, which shocked markets by blending the irrational with strategy. While traditional economists were caught off guard, seeing this as “irrational,” MIT and Stanford researchers argue these moves reflected a deeper strategic shift: a departure from absolute welfare maximization toward relative economic gain.

This pattern mirrors historical cycles. In the period before World War I, nations turned to protectionism and bloc economies. After World War II democracy and liberal economics prevailed. The 1980s ushered in neoliberalism. Today, however, we see a return to economic statecraft, combining elements of military Keynesianism—where governments deploy industrial policy and strategic control over trade and finance—as governments seek to bolster national resilience and counter foreign dominance.

2. Hegemonic Nodes: Manufacturing vs Finance

A useful way to make sense of modern geoeconomics is to examine how states leverage hegemonic control over economic “nodes.” A think tank known as the Global Capital Allocation Project (GCAP) frames the U.S.-China rivalry with this lens:

China dominates manufacturing, especially in sectors like rare earths, solar panels, and high-capacity production.

The U.S. controls global finance, particularly through the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

The result is a tense strategic interplay: the U.S. seeks to undermine China’s manufacturing edge through tariffs, export controls, and subsidies, while protecting its own “financial hegemony” through dollar dominance and monetary policy. Technological dominance—whether in semiconductors, AI, or clean energy—remains another contested node. The message: in geoeconomics, wealth and influence are anchored in systemic control.

3. Global Ripple Effects: The Rise of Statecraft

Geoeconomics is not just a U.S.-China story—it ripples through every corner of the global economy. In response to escalating tensions, many nations are crafting “anti-coercion strategies.” In the U.K., this has revived debate about wartime economic playbooks—including a re-examination of a 1938 “Handbook of Economic Warfare”—to prepare for trade disruptions or hostile economic campaigns.

Moreover, governments and corporations alike are shifting to strategic statecraft: companies are even considering the role of a Chief Geopolitics Officer to steer them through power-based economic landscapes, where governments are no longer neutral referees but active players.

This shift reinforces the need for businesses to navigate a complex web of sanctions, export controls, subsidies, and national security policies. It also challenges a central neoliberal assumption: that economic self-interest naturally aligns with global welfare. Instead, nations are prioritizing relative power over absolute gains.

4. Industrial Policy Makes a Comeback

One of the most visible manifestations of geoeconomics is the resurgence of industrial policy. Long dismissed in many Western capitals, it has returned under both Trump and Biden:

In the U.S., a flurry of trade tariffs has been coupled with domestic industrial strategies, including investment in domestic semiconductor production (e.g., the CHIPS Act) and clean energy incentives.

Europe is similarly exploring industrial revitalization. Economists like Marc Fasteau and Ian Fletcher are advocating for protectionist measures akin to successful East Asian development strategies.

Other nations—like Japan, Saudi Arabia, and the EU through initiatives like the Digital Euro—are also asserting techno-economic sovereignty.

State-directed investment, strategic incentives, and industrial champions are back in vogue. The goal: reduce reliance on foreign-made critical tech while creating domestic economic resilience.

5. The Stakeholder-State Alignment

Geoeconomics is redefining the relationship between business and state. Traditional neoliberal doctrine, championed by Milton Friedman, encouraged shareholder primacy—maximize profits, and political questions were secondary. But fast-forward to today, and even criticisms of ESG movements are not advocating a return to pure shareholderism. Instead, critics are demanding a more strategic, stakeholder-aware capitalism, where businesses align with national security, cultural norms, and technological sovereignty.

This blurs the line between corporate strategy and national interest. CEOs are now expected to evaluate which stakeholders matter—shareholders, national governments, allied states, and diverse societal groups. In other words, business decisions are increasingly political decisions—whether consciously or not.

6. Is This Temporary—or a Long-Term Trend?

Critics argue geoeconomics might be a transient political backlash tied to the Trump presidency. But we urge caution. Historical precedent suggests these shifts persist for a generation—a decade or more—not just a few years.

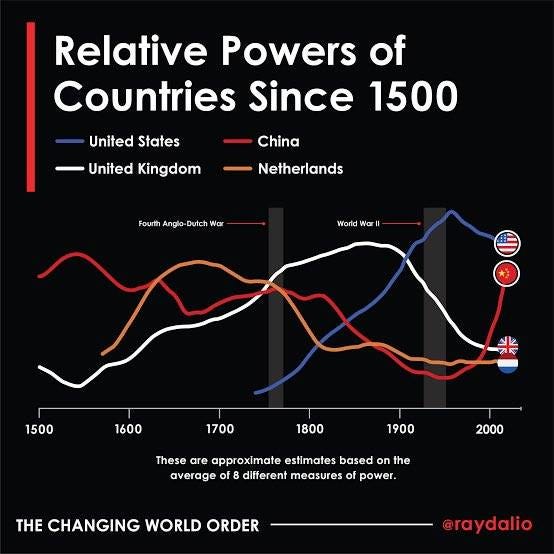

Ray Dalio, whose evolving analysis now includes geopolitical cycles, frames today as part of a multidecade debt-geopolitical cycle, echoing the rise and fall of other world powers. The lack of political consensus—even inside the U.S.—on how to navigate debt, industrial strategy, and global relations reinforces the need for structural adaptation

.

7. The Stakes and Risks

Geoeconomic competition carries inherent risks. Fragmentation of global supply chains—referred to as “friend-shoring” or “de-risking”—inhibits integration and raises costs. Protectionist policies may spark retaliatory tariffs, hurting consumers and businesses. Cross-border investment flows could decline, especially in emerging economies.

Similarly, the weaponization of financial systems—through sanctions and trade restrictions—may reward dominant powers but also fuel political polarization. Nations adopting geoeconomic tactics force others to choose sides or face coercive damage. Again, history suggests such fragmentation can entrench over decades.

8. Strategic Adaptation Is Mandatory

We suggest that governments, businesses, and global institutions must embrace geoeconomics strategically. Companies should appoint geopolitics officers, diversify supply chains, and integrate industrial policy into core planning. Nations must blend diplomatic alliances with technical sovereignty—whether via digital currencies, semiconductors, or climate tech.

Multilateral institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and G20 should adapt to this new reality. A reimagined global governance must balance economic interdependence with strategic resilience, offering frameworks that discourage coercion while fostering competitiveness.

9. The Future We Face

In closing, We say- geoeconomics is not a passing fad, but a structural transformation of the global system. Scholars and institutions—from Stanford geoeconomics projects to IMF programming—are racing to understand and theorize this evolving terrain.

For readers—from students to CEOs to policymakers—the imperative is clear: we must learn to operate in a world where politics shapes markets as much as markets shape politics. The intellectual pendulum has shifted. Whether we resist or adapt, it's time to master the mechanics of the new age of geoeconomics.